Travel diary – Embassy To Samarkand Uzbekistan – Miquel Silvestre

Today we bring to you an exclusive on Wheelsguru.com – Epic adventure rider, moto-journalist and world traveller, Miquel Silvestre‘s Travel Diary – Embassy to Smarkand (Uzbekistan)

Below is the excerpt of the same that he did on BMW Motarrad GS1200R for Adventuremotorcycling.com ‘s magazine –

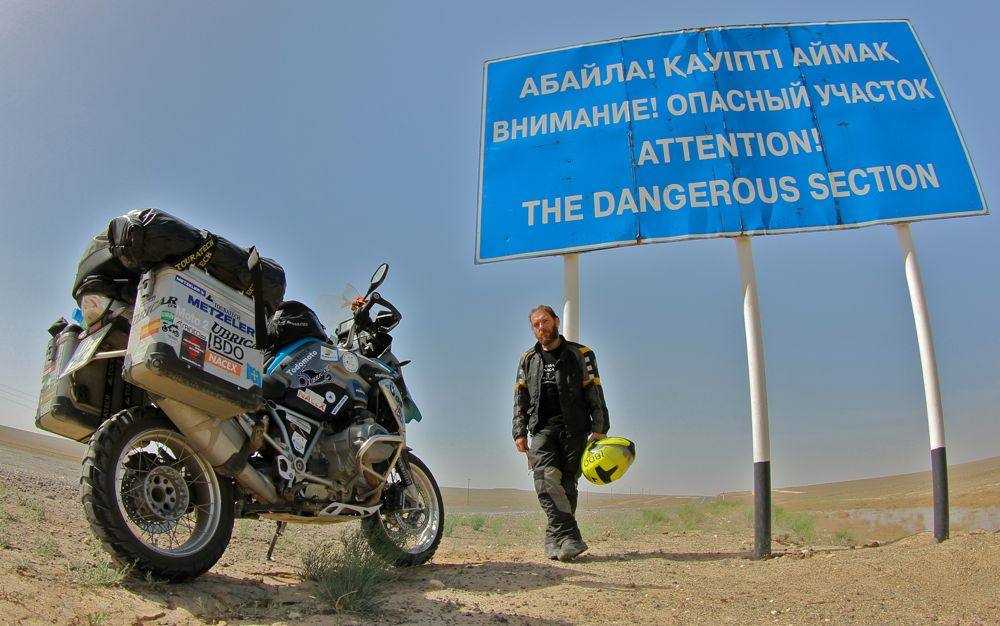

KAZAKHSTAN, THE HELL

Customs at the Uzbek border consisted of a dirty rectangular cubicle, two by three meters. Within the rough concrete building was a rickety chair, a dilapidated and wobbly pressed-wood table, a gray file cabinet, three windows covered with generations of dust, and an elongated billboard with phrases taken from the Koran hanging crooked on a shelf. Lying on a neighboring shelf was a chunk of unleavened bread, a blackened kettle, two hundred flies, and a radio emitting an endlessly atrocious stew of music—a mix of electronic pachanga disco beats fused with the wailing of traditional Asian songs.

I stood, awaiting a temporary import visa for my motorcycle. Beside me, a group of military and civilians argued loudly, making quite a fuss. There’s something about the way they wear their uniforms that destroys any possible semblance of authority. Perhaps it’s their footwear? I couldn’t help but notice that the military and police never wear boots. Instead, they use low quality worn shoes, often with sharpened toes, angled somewhat upward, with heels crushed down in a way that suggests they’d be easy to remove.

Meanwhile, the customs officer attending me was a young guy, really friendly, who spoke quite acceptable English. I guess that’s why they entrusted him with the care of foreigners who’d chosen the worst possible way to enter Uzbekistan from Kazakhstan. Apparently, I’d arrived using the worst of the worst—a road that begins in Aktau, on the shores of the Caspian Sea, and crosses the endless desert all the way to this lonely border outpost. Normally, drivers who come from Turkmenistan, or the Kazakhstan city of Atyrau, find a more reasonably paved road.

I had that hell of a desert all to myself. From Aktau to Beyneau there are 470 miles of dusty barren plain. One heck of a lot of potholes, dust, sand as fine as talcum powder, and cratered rock, that had my bike rattling in a horrible way—as if it was going to disintegrate under me. It was such a struggle to get here that I began to wonder what was the point of doing all this. The answer, I found, was to stop asking myself these questions, and just get on with it.

The customs officer asked the usual questions about the power, year and the value of the bike. Around here, this seems to be the norm. Sometimes, to avoid giving the impression that I’m wealthy (which I’m not), I tell them the lowest price I can think of. I could just as easily half the price of what it costs, and it would still represent an exorbitant amount for most of the people here. Other times, I declare an absurdly high value, like a million dollars. The result in either case is always the same: Misunderstanding and astonished faces. But, this time I declared the exact price to the official. He paused for a moment from tapping away at the keyboard, then said, “Why?”

“Why what?” I inquire.

“Why have you chosen this way of traveling: Alone, dangerous, and difficult? You could come here by plane.”

I had an answer—not so much for him, but for me. It may seem quite stupid to expose oneself to danger, and the guaranteed discomfort that comes with the territory. So much so, that I once gave a talk titled, “Manual for an Idiot Adventurer,” about my travel experiences. The reason behind that title had not so much to do with the fact that I consider myself a complete disaster at planning and organizing my own adventures, rather that only well fed Westerners pay to get into struggles like these. I knew that my work as a writer was just another consequence of the comfort society in which we live. A society from whence we flee so we can return.

In other words, I knew that I needed to feel the cold in order to enjoy the heat, to be hungry enough to be delighted by a dry crust of bread at the end of a hard day, to be thirsty so I could recognize the sweet taste of drinking water… I needed to test myself, to overcome obstacles and share the process with others.

“I do it because it’s worth it,” I replied. I came here meter by meter, rock by rock, to take possession of the cities along the Silk Road. As I enter each city, I will make it mine, and will feel increasing camaraderie with the Spanish explorer for whom I make this journey.

UZBEKISTAN, THE BEAUTY

Khiva, the Ancient Walls

Khiva is about 500 kilometers from the border. The road from Kungrad is nice, acceptably paved, and runs parallel to the fertile plain of the Amu Darya River. The channel, entrusted with giving life to the desert, helps me forget the terrible passage through the deserted Kazakh. As I cross the river by way of an unstable bridge, I spot the city walls—like a vision of something from the Arabian Nights.

For twenty dollars a night, I stay in the hotel Islambek, situated within the city walls in a section called Itchan Kala. That evening, as I got lost within the narrow streets and passageways of Khiva, I discovered a wonderful place… a jewel in the desert, an oasis full of beauty, surrounded by a wall that served as a superb way station to the camel caravans of the past that were heading to Persia. The independent kingdom of Khiva resisted Russian invasions until the late Nineteenth Century, when its independence finally succumbed to the Tsar in 1877.

Bukhara, the Lively City

I head east. Again, the desert. Again, the horrible bumps. Again, the police checks. However, this part of the country is so remote, desolate and sandy that the rigor of the custom agents is minimal. No one comes here. It’s a cracked landscape, where the sand tries to eat the narrow asphalt path. The horizon shines yellow, leaden, inexhaustible.

After an endless day of heat and defensive riding, I arrive at the outskirts of Bukhara. The new neighborhoods surrounding the city, with their sterile Soviet-style concrete block edifices, are so ugly that little do I anticipate the magnificence of the ancient city within. Bukhara may be the most beautiful city on our planet. Populated by Tajiks, it’s a unique place even for the Uzbeks themselves, who make pilgrimages to pray at their temples, and study in its Madrasa, one of the oldest in Central Asia.

To walk through the stunning beauty of the ancient city shakes even the most phlegmatic person. It’s awesome and impressive. Carved doors, a market streaked by narrow passageways and crannies, a big mosque and an astonishingly perfect stylized minaret named Kalyan. This is certainly one of the most charming historic sites I’ve ever seen. I feel the most intrepid explorer. This is real, it’s happening… I’m walking The Silk Road, and although this could be only a romantic legend, my excitement is genuine.

Towards Samarkand

I leave the monumental that is Bukhara, and ride towards Samarkand. The trip seems endless due to my anxiousness to arrive. But, just as tiredness begins to overwhelm, I’m welcomed by a huge sign that reads “Samarkand.” I jump for joy

The city is magical, beautiful, amazing. Unlike its Kazakh neighbors whose nomad shepherds never built anything more stable than a yurt (a traditional circular tent of the steppe), the farmers of Tajik founded the fertile valleys filled with cities that embrace blue mosques, high minarets and immense monuments. And, they also founded the mighty Timorese Kingdom, of the Great Tamerlane, who in less than 10 years conquered Iran, Iraq, Syria and Eastern Turkey. After a breakfast of unleavened bread and cucumber, I go outside into the Registan, a square located opposite the Grand Mosque. The atmosphere is of quiet and peaceful retreat. The buildings are of spectacular beauty, so astonishing that it almost hurts. A young man approaches me and starts a conversation. I’m not in a hurry, so we chat for a while. I share with him my scarce historical knowledge of the Great Court and its monuments. I tell him I’m only interested in one thing, and if he knows about it, and there was any trace left, I will hire him as a guide to show it to me.

“All right,” he accepts.

“I’m seeking the traces of a Spanish ambassador who came here in the fifteenth century,” I reply.

’m convinced that he has no idea of the Castilian and Spaniard Ruiz González de Clavijo from those bygone days. Just as I begin to feel that my proposition may have been accepted a little too quickly, the kid’s eyes light up. He assures me enthusiastically that he does know. There’s something more than just financial interest in his joy—behind it is a scholar’s pride. He tells me that there was hardly anything left, barely a street with a strange name, but he knew where it was, and also some of the history behind it. He had discovered it by chance one day, about five years ago. Interested in the strange name, he sought information in books.

We walk towards the mausoleum of Gur Emir, where Timor the Great is buried. Sure enough, the street plate is still there. It is true! Clavijo—Klavixo for Uzbeks— has a street in Samarkand. There is a piece of Spain in Uzbekistan!

In 1403, Rui Gonzalez de Clavijo was sent to Central Asia by Henry III, king of Castile (Spain). His goal was to close up a partnership with Tamerlane to fight against the Turks. He crossed by Rhodes and Constantinople (now Istanbul), before entering the Black Sea, disembarking in Trabzon. From there he continued overland through Iraq and Iran to reach Samarkand on a journey that, even today, still intimidates by its risk and harshness. When the unexpected traveler appeared in Timor’s court, he was received with delight and ceremony. But, after Timor’s death, a period of instability began as his heirs divided the empire among themselves. Clavijo’s embassy could be labeled a diplomatic failure. However, the success was the journey itself, a feat that surpassed his mission’s goal. And to this day, his book, Embassy to Tamerlane, is a landmark in medieval travel literature.

I owe to Clavijo the existence of my own adventure. He gave all of us a portrait of a time and place that no Westerner knew before. He represents the reason why I continue traveling. Great journeys exist because there are chroniclers—those who share with us their travel stories. Without them, only dust would remain.

Below is another of his travel Diary – Backtracking History of East Africa

About the Author:

Miquel Silvestre is a fine example of someone that escaped the chains, got off the treadmill, and changed the direction of their life completely, to dedicate their time on this planet to inspiring others, in the pursuit of their dreams.

Follow him on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram